All legitimate authority requires a a “master narrative” with which to define itself and make its claims stick, and the instability of the Revolution is attributable partly to the fact that the French could not reach consensus about the nature of that story. Having rejected the charisma of the king as the basis of political legitimacy, revolutionaries went looking for stories and images that would legitimate themselves in a new way.

During the phase of “constitutional monarchy” (1789-1792) it was still possible to adapt the symbols of the pre-revolutionary France to the new circumstances. Thus Louis XVI could be represented as a leader of the Revolution. As the events of 1791 and 1792 revealed, however, revolutionaries found it increasingly difficult to agree on what shape the new order should take. This generated what historian Lynn Hunt has called a “crisis of representation”—a fundamental conflict over the nature and content of political symbolism in the new revolutionary order.

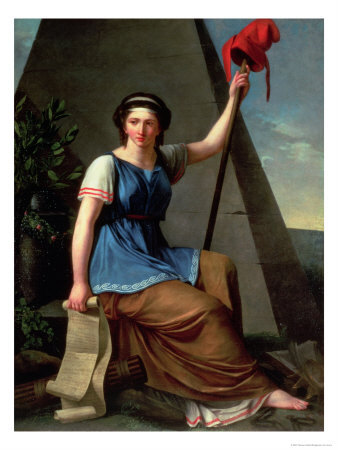

The first solution to this problem was “Marianne,” as she came to be known, a feminine personification, or allegory, of liberty. She is a familiar figure: in the European tradition, the habit of representing abstract, civic virtues or principles of government in the form of serene woman is of ancient origins. The most vivid versin of “Marianne” was painted by Nanine Vallain, a protégé of Jacques-Louis David, painted in 1792, which hung in the meeting house of the Jacobin Club. She holds the staff of authority; on top of it is the Phrygian cap of liberty; the Egyptian pyramid behind her gestures toward the universalist and Deist norms of the Enlightenment. The scrolls in her right hand, finally, underscore the role of legislation in defining her power. But she is not aggressive; Marianne is peaceful and poised. In a slightly different pose, Marianne also graces the first official Seal of the Republic (1792). In time, Marianne became the dominant figure of republican liberty.

Image right: Nanine Vallain,

La Liberté (1792), Musée

de la Révolution Francaise de Vizille. Image source: art.com.

During the radical phase of the Revolution, however, her dominance was far less certain. Radical republicans found Marianne inadequate because she was far too imprecise symbolically: she was, essentially, as symbol of the nation, not a statement about France’s political order. They wanted a symbol that was much more explicit about the authority of the People and the republican nature of revolutionary France; in 1793 and again in 1794, several members of the National Convention suggested replacing Marianne with Hercules.

The engraver Dupré suggested a new icon: a giant Hercules would hold Marianne and the personification of Justice in his right hand. The change in gender is significant: like “Prudhomme,” many radicals believed that the Old Regime had been corrupt because of the influence of women at court. For them, this was an intolerable state of affairs, one that violate the proper place of women according to Natural Law. In other words: the femininity of Marianne made her problematic: she contained too much of the Old Regime.

The very masculine Hercules was also a symbol of republican unity in a particular and a general sense: first, Hercules symbolized the unity of the nation over rebellion and counter-revolution in the provinces. Other versions of Hercules show him crushing the monstrous “Hydra of Federalism,” or devouring the monarchs of Europe.

In a more general sense, Hercules symbolized what democracy was all about. For radicals, “democracy” was an idea that did not tolerate division: on the contrary, their overriding tendency was to think about politics in oppositional, conspiratorial terms—“on the one side, democracy, the people’s will, the Revolution; on the other side, the plot, the anti-principle, the negation.” For Radicals, political parties or “factions” could only stand for the “particular,” not for the General Will. In this sense, political division was a form of counterrevolution. In this more fundamental sense, the serene Hercules stood for the General Will of The People, smashing “conspirators” with his terrible club. This also gets at the meaning of the Terror for the Radicals: for them, the Terror was the purest expression of republican virtue against its enemies. It represented the final destruction of the Old Regime and everything associated with it.

.jpg)